Declining healthcare

Mother and daughter: Lizketseng Lesaoana, 25, half an hour after delivering a baby girl at Queen Elizabeth II Hospital in Maseru, Lesotho. They lie on a plastic sheet that is cleaned with a damp cloth between births. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Nursery: A newborn is placed on a table at Queen Elizabeth II Hospital in Maseru, Lesotho. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

A moment of rest: Midwife and nurse Lillo Kuape pauses next to a table of babies at Queen Elizabeth II Hospital in Maseru, Lesotho, after trying for hours to save Matsepang Nyobas baby girl Mankuebe. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Struggling to breathe: The nursery of the Queen Elizabeth II Hospital in Maseru, Lesotho, had only one working oxygen valve. Nurses used plastic hoods connected with rubber tubing to share the single flow of oxygen among as many as six sick infants. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

A mothers touch: A woman tends to her tiny newborn in the nursery of Queen Elizabeth II Hospital in Maseru, Lesotho. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Struggle to survive: Nurse-midwife Lillo Kuape rushes barely breathing newborn Mankuebe Nyoba to the intensive-care nursery at Queen Elizabeth II Hospital in Maseru, Lesotho. No oxygen was available, and the baby died a few hours later. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

At a loss: Matsepang Nyoba, 30, slumps on a thin mattress in her one-room rock and mud house, two days after her newborn daughter died at Queen Elizabeth II Hospital in Maseru, Lesotho. Asked about her familys future, the woman, whose given name means mother, have hope, sighed deeply and replied, I honestly dont know. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Mourning rites: Using an antiquated razor dipped in soapy water, Mampho Mofa shaves Matsepang Nyobas head in Maseru, Lesotho, as part of ritual grieving. Two days earlier, Nyobas baby girl Mankuebe was born and died in the roach-infested maternity ward of Queen Elizabeth II, a crumbling sprawl that is this remote nations largest hospital. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

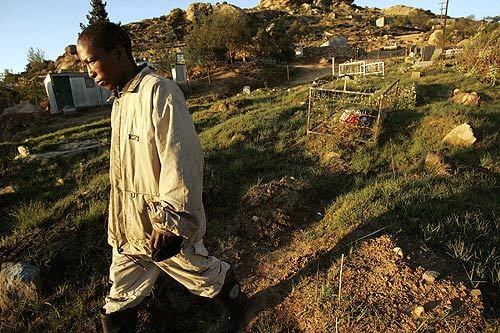

A fathers grief: Peo Nyobas baby girl died hours after she was born at Queen Elizabeth II Hospital in Maseru, Lesotho. Her father, a security guard, borrowed money from his boss for the unexpected expense of the unmarked grave and morgue fees. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Expert touch: Dr. Jennifer Furin, center, and nurse David Kolobe, right, examine Teboho Mahate, 14, at a government clinic operated by Partners in Health in the remote mountain village of Ha Nohana, Lesotho. The boy was diagnosed with life-threatening meningitis but recovered after treatment. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Refuge for the sick: Dr. Jennifer Furin examines Teboho Mahate, 14, at a government clinic operated by Partners in Health in the remote mountain village of Ha Nohana, Lesotho. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

In good hands: Nurse David Kolobe carries Teboho Mahate, 14, after a spinal tap at the Partners in Health clinic in the remote mountain village of Ha Nohana, Lesotho. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

A mothers fear: Josephine Uwimana holds her 10-month-old son, Jeremiah Bizimana, at the Social Medical Center in Kigali, Rwanda. She feared that the feverish baby had malaria, but his lab test showed no evidence of the disease. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Standing room: A young boy mimics his elders at a crowded AIDS clinic in Maseru, Lesotho. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

It hurts for only a minute: Children receive immunizations for measles, supported by the GAVI Alliance and managed by UNICEF in Semonkong, a small village near the center of Lesotho. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Self-reliance in action: An association of HIV-positive people and their supporters prepare a field on the grounds of a hospital operated with the government by Partners in Health in Rwinkwavu, Rwanda. The group planned to feed its members and families from the beans and corn grown there. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Working for the future: Members of a cooperative of HIV/AIDS patients and supporters tend their fields in the hot African sun in Rwinkwavu, Rwanda. They are part of a program to promote self-reliance by Partners in Health, an NGO that works to improve public-sector health services. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Journey for her pills: AIDS patient Malerotholi Moleko, 41, travels home in a crowded bus to her rural village, about a 30-minute drive out of Maseru, Lesotho. The ride costs $3.25 more than the average daily wage from her job washing clothes. Moleko supports eight children four of her own, and four from her late niece. When she cannot afford bus fare, she does without her medicine. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Long walk home: Sheep graze in the rugged pasture as Malerotholi Moleko, 41, walks back to her village of Sefikeng, Lesotho, after the bus ride from the hospital for her AIDS treatment. Sometimes she barely makes it. Moleko is weak because most days her family eats only pappa, the staple cornmeal mush. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Pills without food: Thanks to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, Malerotholi Moleko, 41, gets free HIV medication. Her problem is hunger. After Ive taken the pills, my appetite becomes bigger, and I dont have the food, she said, hoisting her nieces baby on her back in a colorful blanket. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Moment of calm: Anna Tebello, 14, does her homework, while Malerotholi Moleko washes dishes at their home in Sefikeng, Lesotho. Moleko takes care of eight children four of her own and four from a niece who died of AIDS this year. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Rugged lives: A view through Malerotholi Molekos kitchen window reveals her son Lerotholi Abiel as he tends to grazing cattle in Lesothos barren mountains. He works every day, regardless of the weather. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)